Upland Landscapes

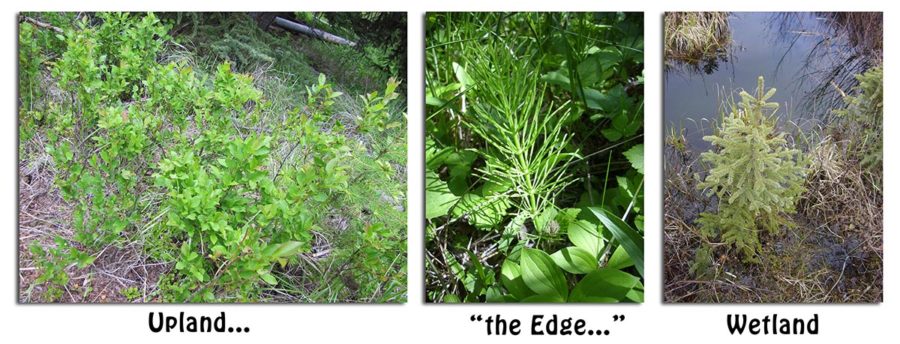

At higher ground in the Preserve, you will notice a change in the vegetation and habitats surrounding you. Click here to view our photo album of the upland ecosystems at the Preserve.

At higher ground in the Preserve, you will notice a change in the vegetation and habitats surrounding you. Click here to view our photo album of the upland ecosystems at the Preserve.

Click here to view our full photo album of the Lost Lake wetlands year-round!

“The wetlands within the Lost Lake Preserve are of high conservation value due to the rare plants and plant communities which occur there and the fact that the site retains excellent ecological integrity despite numerous human stressors in the surrounding landscape. The site supports numerous wetland types such as a calcareous fen, shrub swamp, and forested seepage swamp. Of particular interest is the calcareous fen, which are rare in Washington and are primarily limited to the northeast corner of the State. Calcareous fens are also one of the rarest wetland types in the United States. Calcareous fens differ from other peatlands in that their pH is circumneutral to alkaline and they typically have a high amount of calcium and other base cations. Such conditions result in a unique set of plants which are able to grow in the fen. One of the more significant plant community types found at Lost Lake Preserve is the bog birch/slender sedge (Betula glandulosa/Carex lasiocarpa) plant association. This plant association is typically found in rich to extremely rich fens (e.g. calcareous fens) and is known to occur in northwestern Montana through northern Idaho and into northeastern Washington. Within Washington it is considered to be very rare. In summary, the Lost Lake Wetland Preserve harbors some significant pieces of Washington’s natural heritage. The long-term protection of this wetland complex would contribute to the conservation of these biodiversity treasures within Washington state.”

Joe Rocchio, WA Dept. of Natural Resources

A wide variety of amphibians find everything they need to thrive in the Lost Lake Wetland.

The wetland hosts a healthy population of the State Candidate Species, Rana luteiventris, the Columbia Spotted Frog. This species is abundant in the Lost Lake wetland, though statewide it is ranked by the Natural Heritage Program as “Apparently Secure,” meaning that while they are at fairly low risk of extinction or elimination, there is “possible cause for some concern as a result of local recent declines, threats, or other factors.”

The recently reestablished beaver population in the Lost Lake wetland improves wetland function. Significant increases in the water storage capacity of the wetland caused by beaver activity will not only benefit the hydrology of the wetland and the nesting waterbird and plant populations, but will provide additional water for late season flows into the Myers Creek subwatershed.

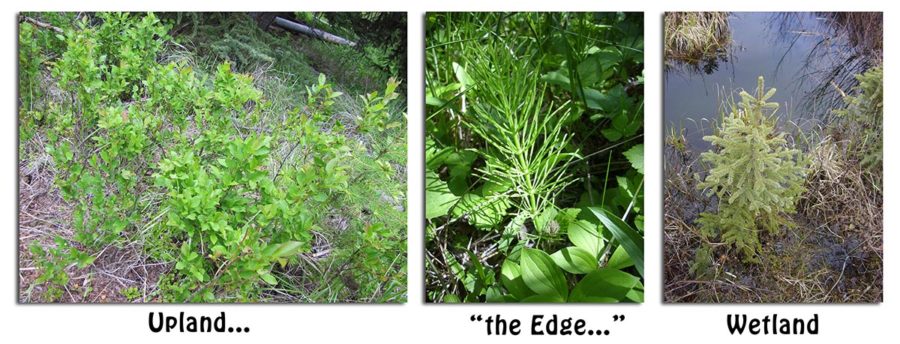

Another waterbird of note that has traditionally nested at Lost Lake is the Black Tern, a Category 2 candidate for listing under the Endangered Species Act, and a bird-at-risk on the Washington Gap Analysis list. According to the Seattle Audubon Society (2008), Black Tern numbers have “decreased since the 1960s due in part to the destruction or degradation of much of their breeding…habitat.”

You may see these black and silver birds swooping to pluck food from the surface of Lost Lake or foraging in flight as they seize flying insects from the air. In order to nest, the Black Tern needs habitat with extensive cover vegetation as well as open water. Like the loon, the small and graceful tern nests on floating debris or near the water, making the Lost Lake non-combustible motor rule a key factor for successful nesting for both species.

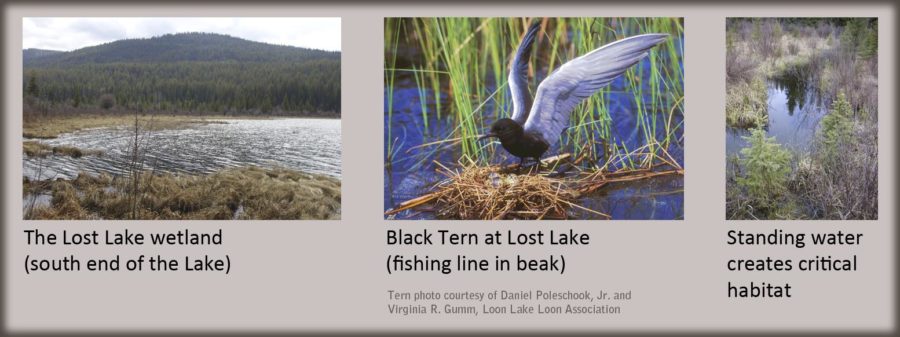

Community involvement is also needed to protect nesting waterbird populations. Of particular interest is the Common Loon (Gavia immer), a rare breeder in Washington and a sensitive species ranked as imperiled in the state. More Common Loon chicks have been produced on record at Lost Lake than any other lake in Washington. While Lost Lake has historically been a successful nesting place for Common Loons, the loon population is in jeopardy.

Beginning in the 1980’s, lifelong area resident Roy Visser began observing nesting loons and recording their behavior. For fifteen years, Ginger Gumm and Daniel Poleschook, Jr. of the Loon Lake Loon Association (LLLA), with the help of Patti Baumgardner from the USFS, have conducted a study of Eastern WA loons, which has confirmed lead toxicosis as a cause of loon death at Lost Lake and as the cause of 39% of all loon deaths in WA State.

View and compare data for WA Common Loons, compiled by Daniel and Ginger Poleschook (Excel spreadsheets):

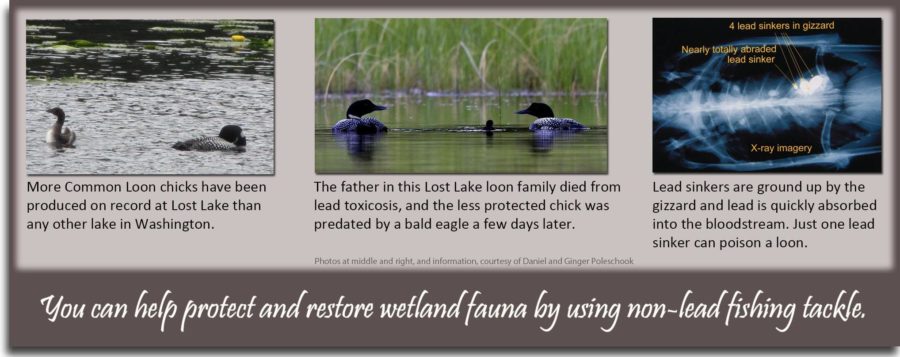

According to the LLLA, loons most commonly take in lead by ingesting fish on an active or broken fishing line. Additionally, when loons scoop up pebbles from the bottom of the lake to help grind their food, they can swallow lead fishing sinkers. Terns, geese, dabbling ducks, swans, mergansers as well as small mammals can also be poisoned, and the lead moves through the food chain, affecting eagles and other predators. A bird with lead poisoning cannot keep balance, breathe or fly properly, adequately eat or care for young, and often dies within two to three weeks. Just one lead sinker is enough to kill a loon.

In December, 2010, the Washington Fish and Wildlife Commission approved restrictions on the use of lead fishing tackle at 13 lakes with nesting common loons, including Lost Lake. Please help spread the word that lead-free tackle must now be used at Lost Lake, and help others understand how important this is to wildlife. Lead is also toxic to humans; a piece of lead as small as a grain of sand is enough to poison a child (Centers for Disease Control, 1991).

Click here to view our gallery of the different sedges seen at the Lost Lake Preserve! Then, click on each image to enlarge and discover each plant’s common and scientific name!

How do you distinguish different grass-like plants? Remember the rhyme!

Sedges have edges, rushes are round, grasses have nodes all the way to the ground!

Click here to view our gallery of wildflowers seen at the Lost Lake Preserve–these include terrestrial, wetland, and aquatic flowering plants! Then, click on each image to enlarge and discover each plant’s common and scientific name!

Click here to view our gallery of the trees and shrubs seen at the Lost Lake Preserve! Then, click on each image to enlarge and discover each plant’s common and scientific name!