Flying Squirrels

Flying squirrels help the forests they live in!

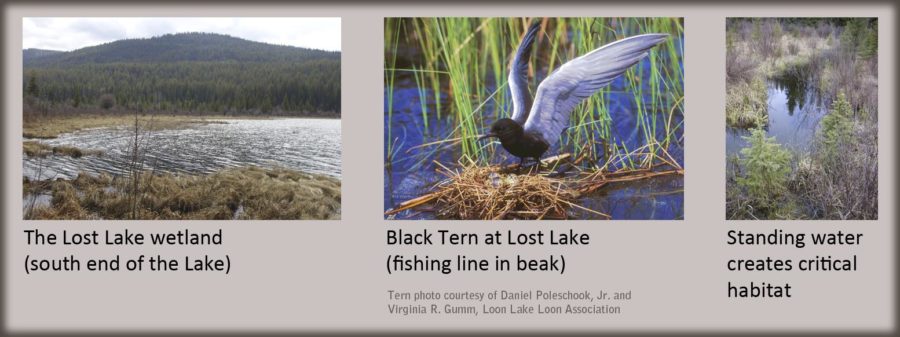

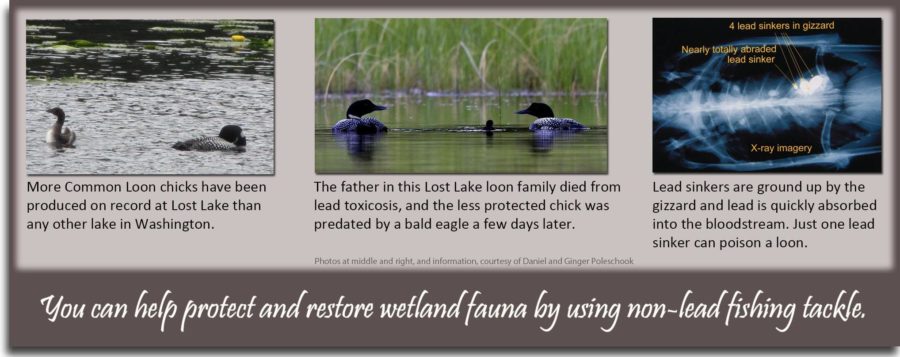

Truffles, also known as hypogeous fungi, live a mysterious existence, fruiting below ground in the mineral soil/organic layer interface. While their mushroom relatives fruit above ground and loudly display their wild array of colors, textures and shapes, truffles quietly play out their important roles out of human sight. Truffles provide food for various mammals (and in turn the predators), and their mycorrhizal fungi networks contribute to the health of certain trees, including Douglas-fir. Flying squirrels are adept at hunting for truffles, drawn by the aroma. The truffle spores and bacteria pass through the squirrels’ digestive tracts, ready to colonize the roots of nearby trees and understory plants with mycorrhizal fungi.

“Mycorrhizal fungi enhance the ability of trees to absorb water and nutrients from soil, and they move photosynthetic carbohydrates from trees into the soil,” explains Andy Carey, former research biologist with the Pacific Northwest Research Station in Olympia, WA. “In turn, this carbon supports a vast array of microbes, insects, nematodes, bacteria, and other organisms in the soil.1” Fungal networks actually “take up minerals and water from soil and transport them into the fine feeder roots for use by the host plant.2”

Several species of truffles grow in Eastern WA, when fir, pine, hazelnut or other tree species establish mycorrhizal relationships with truffle-forming fungi species. Squirrels and other forest-dwelling mammals play an essential role in dispersing fungal spores, thus helping to complete the web of life in the forest. “Truffle species also perform many important ecosystem functions including organic matter decomposition, nutrient cycling and retention, soil aggregation, and transferring energy through soil food webs. These functions contribute to the overall health, resiliency, and sustainability of forest ecosystems.2”

1. Science Findings, Issue 60 www.fs.fed.us/pnw/sciencef/scifi60.pdf

2. Diversity, Ecology, and Conservation of Truffle Fungi in Forests of the Pacific Northwest, Trappe et al, www.fs.fed.us/pnw/pubs/pnw_gtr772.pdf

Supporting the Northern flying squirrel is one way that natural resource professionals are working to recover the threatened spotted owl. Learn more:

www.fs.usda.gov/treesearch/pubs/44793

www.fs.usda.gov/treesearch/pubs/5525

Read the lyrics to our song about fungi and flying squirrels on the Wild Mushrooms and Fungi Ecology event page.